|

Delphi is probably the most famous oracle in the world. It’s awe-inspiring. Sublime. Superhuman. Intoxicating. These are only a few of the adjectives that immediately come to mind when, after a long climb, you reach its perch on the slopes of Mount Parnassus. You do feel superhuman, standing above the world: behind you the temple of Apollo; in front, the world of ancient Greece emerging from the unfolding landscape like a forgotten idyll.

There are two legends about how the oracle functioned. One comes from the deep recesses of the archaic Earth Goddess religion; the other belongs to the epoch of the male-based world-view, when the sun god Apollo slew the serpent Python, the son of the goddess, and usurped the shrine. (Serpents and dragons are symbols of energy currents that glide in serpentine fashion through the earth’s crust, hence they are symbols of ancient Mother Goddess traditions.) A prerequisite for an oracle is the existence of a cavern, a crack, a fissure—any kind of opening in the earth that brings to the surface the influences of the Earth Goddess, usually through vapors that seep through the opening. In ancient Greek, delfos means “womb” or “vagina.” In Delphi, there was one such cleft rock near the Castalian Spring, from which oozed intoxicating vapors. The officiating priestess crouched over those vapors that would affect her psyche so that she became a conduit through which the oracle “spoke.” When Apollo killed the Python and took over the oracle, he also diverted the prophetic influence from this cleft rock to the omphalos stone (also known as “the navel of the world”) where his temple was subsequently built. Over the entrance were carved the famous maxims: “Man, Know Thyself” and “Nothing in Excess.” And above the temple is located the theater, where the famous Pythian Games were held—as if in the clouds. Everything that is extraordinary about Delphi seems to gather here, where the charioteers run their steeds, delineated, superhuman, against the violet sky.

0 Comments

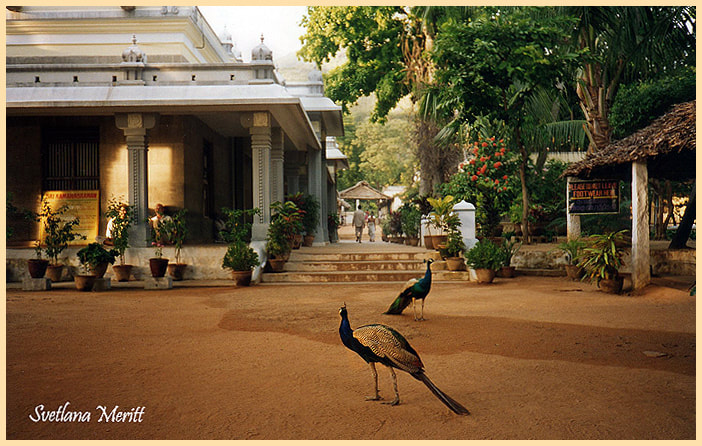

Sixty years after the death of Ramana Maharshi, one of the greatest Indian teachers, his ashram still attracts throngs of devotees from all over the world, and is considered one of the great spiritual centers of India. The temple complex is located (unfortunately) on the main road to Tiruvannamalai, a busy town in Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India.

Once you wade through the onslaught of beggars and the barreling buses, trucks, cars, rickshaws, and bicycles—all blaring horns to announce their presence—you enter the quiet bustle of the ashram precinct. A majestic banyan tree protectively shades the front courtyard. Among tropical trees and flowers stroll peacocks, jump chattering monkeys, fly exotic birds, all of which gives the impressions of Paradise before the fall. But all the commotion of the outside world is erased as if by a magic wand as you step into the old meditation hall where Ramana used to spend most of his time in meditation, reclining on a couch in a corner. Even the chatter of your mind is stilled as if by some outside force, and you sink into a state of intense peace. This is the most charged area in the whole ashram. Two new shrines, which house marble tombs of Ramana and his mother, didn’t do anything for me. In the sharp neon light, devotees circle around the tombs, chanting songs of worship to their guru and his mother. I was twice reprimanded for breaking the temple rules and offending gods. First for smelling the flowers used to make garlands for ritual offering (they were discarded after I smelled them), then for sitting together with Dwight in the part of the hall reserved for men (I had to move to the side allotted to women). To get away from the petty rules—imposed after Ramana’s death, to be sure—we climbed the sacred hill of Arunachala that looms above the ashram. There, in caves, Ramana spent the early years of his life before the ashram was built. From the upper cave, shielded by a mango tree, the view extends over the whole of Tiruvannamalai and the plains beyond. In the inner sanctum, so small that only two people can meditate at the same time, a large picture of Ramana still evokes his presence. In the flicker of one candle, his eyes glow as if alive. I lost myself gazing into his eyes, and a deep sense of serenity and peace enveloped me. Given its history, I’m not sure this castle would qualify as a sacred site; but the View of Rome from its top terrace, just below the angel, would definitely inspire you. In my personal list of requirements for the sacredness of a place, the view plays an important role: it can be revealing, uplifting, transporting, dramatic, spectacular, or breathtaking. But whatever its quality, it will inevitably touch something in you.

That’s why I have included the Angel’s Castle in my photolog of sacred places. Once you go through its history—from its initial function as a mausoleum for the Roman emperor Hadrian, through the medieval transformation into a fortress where the popes would run for their lives from the nearby Vatican, to its present fame as one of the locales where Dan Brown has placed the action of his Angels and Demons—then you can open to the pulse of the place and feel how it affects you. I definitely felt something of the sacred quality standing on the top terrace, with the figure of the angel towering protectively above me, and the roofs of Rome, the dome of the Pantheon, the belfries of many dozens of churches, the Tiber, the bridges, and the Vatican all spread out before me. The history of Western civilization written in brick and stone.  The sacredness of Chartres goes way back to Neolithic times. The first dolmen was placed atop the mound many thousand years ago to mark the spot where the Great Mother was venerated. Fast forward several thousand years to the time of Julius Caesar. In his Gallic War, he recorded that the Druids established their yearly conclave and Druidical college at the very site. Chartres was then the geographical center of the territory inhabited by the Celtic tribe called Carnutes. Fast forward again several hundred years to the twelfth century and the erecting of the famous Gothic cathedral at the spot. The cathedral incorporated the ancient dolmen as well as the sacred Druidic well and the early Christian worship of the Black Madonna. It was also built according to the principles of sacred geometry, with a specific purpose of altering the consciousness of those who enter. This was done through the use of precise ratios in elevation and proportions to give the cathedral properties of a tuned, resonant chamber. Add to this the quality of light created by the famous stained glass windows (the alchemical formula for producing those numinous colors has been lost, and never since have those colors been reproduced), and you get the idea why Chartres was the most sacred site in France. But wait—I forgot to mention the famous labyrinth in the nave … walked by the pilgrims of all ages—at least until recently, when the church authorities put a stop to this meditative practice and covered it by chairs. Dwight and I had the good luck to be accidentally locked in the crypt below. I say “good luck” because the crypt is not open to individual visits. It was a true gift to be alone there (even if we had to bang chairs on the doors to be rescued). How this happened and what we experienced in the dark place of the Black Madonna worship, you can read in my spiritual travelogue--Meet Me in the Underworld: How 77 Sacred Sites, 770 Cappuccinos, 26,000 Miles Led Me to My Soul.  The Royal Abbey of Fontevraud in the Loire Valley in France is an example of what happens to the energy of a sacred site when its purpose is degraded—used for a prison, in this case. Built in the twelfth century, Fontevraud was once a prosperous and large abbey (housing up to 700 nuns) and a spiritual and cultural center for centuries. It is still the largest group of monastic buildings in France. The Abbey is also the final resting place of the famous queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, her husband Henri II, and their equally famous son Richard the Lionheart. The Abbey suffered many blows. Its desecration by Hugenots in the sixteenth century was followed by the partial destruction during the French Revolution in the eighteenth century. Finally, what was left was converted by Napoleon into a state prison, which it has remained until recently. Imagine this elegant, lofty nave, crammed with four platforms where a couple of thousand prisoners were jammed in what were called cages à poules, chicken cages. Many others were kept in the dormitories and the refectory, which were also sub-divided using platforms to increase the prison capacity. The result of this, as energy dowsing showed, is a chaotic and frazzled energy field, with dowsing rods trembling and quivering in all directions, as if they had “lost their head.” As I walked around the Abbey, I couldn’t shake off the feeling of heaviness and sadness—in a way, an energy rape. Carnac in Brittany (northwest France) is one of the biggest megalithic sites in the world: over 4,000 stones aligned in up to thirteen parallel lines, reaching over 4,000 feet in length. The stones were set up by an ancient civilization that lived during the Neolithic era (at least 10,000 years BC).

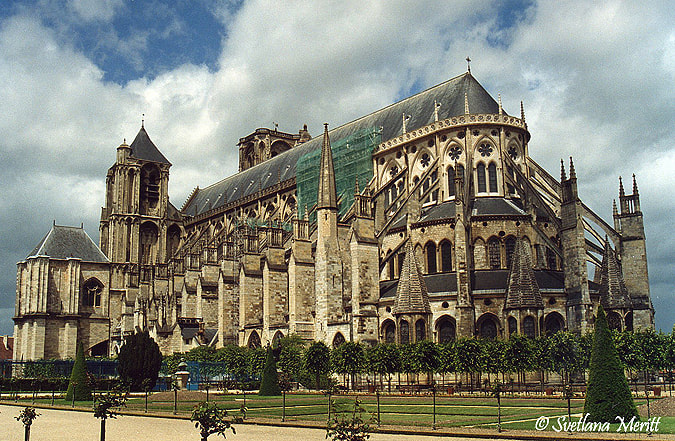

The purpose of the alignments eludes orthodox archaeologists. But many alternative researchers and engineers have explored the megalithic legacy and found a strong connection between the location of megalithic sites and lines of Earth energy. These lines, known as terrestrial or telluric currents, honeycomb the Earth in a manner akin to the nervous system in the human body. The alignments of Carnac were placed over the fault lines of the most active earthquake region in France. As the painstaking research work of Pierre Mereux shows, these stones are electromagnetically active—they are in the state of constant vibration. This finding sheds a completely different light on the “primitive” Neolithic people. I’d say they had a very definite knowledge of Earth’s energies, which they developed into an exact science. About which we—as a superior, technologically advanced civilization—have no clue. Earth science aside, Carnac is a place of great power. Depending on where you stand, the alignments sometimes create the impression of immutable order, rows of stones extending through the countryside like a flock of birds migrating with unerring precision. From other vantage points (like the one in my picture), the impression is of a mass of stones, milling about the field like living creatures. Bourges is a charming, medieval town located at the exact geographic center of France, and as such considered the spiritual hub of the country. Its cathedral, St. Etienne, rises on the site that was sacred to the Celtic kingdom of the Bituriges, who lived there since the 7th century BC.

The Bourges Cathedral is one of the masterpieces of the Gothic architecture, a style that art historians take for granted, without asking the fundamental questions: How come the Gothic appears suddenly, without any period of experiment, and in just a few years reaches its climax? How come the completely new and revolutionary style that appeared so fully developed, suddenly has enough master architects, craftsmen, and builders at its disposal to execute the construction of almost eighty huge edifices in only hundred years—between 1130 and 1230? The answer to what I call “the mystery of Gothic” can be found in the story of an organization that shaped the history of Western civilization to a degree we are not aware of—the Knights Templar. It is speculated that the original band of nine Knights brought from Jerusalem, and more specifically from their digging under the Temple of Solomon, a certain knowledge. A part of it was the principles of sacred geometry—a metaphysical postulates that particular proportions embody a resonance with divine harmony. Walking into this cathedral one cannot but feel the effect of these principles: free of internal enclosures, the interior of the cathedral explodes like a massive forest of pillars, the canopy of which meets in the vaulting at an astonishing height of 115 feet. The whole interior is bathed in soft, evenly distributed light. As we walked in that afternoon, we were blown away by the blast of organ music that hurled mighty sound throughout the vast interior. Imagine: space, light, and sound, unified in this architecture, at the very moment when we stepped in... But the Bourges Cathedral is special in another way. It is located above the crossing of the earth energy currents. The places of crossing, called the nodes, are powerful energy sites. Combined with the architecture embodying geometric proportions that reflect celestial geometry, these places are perfect settings for the communion with the divine. Which is what happened to me in this cathedral. The seventh-century BC capital of the Celtic tribe Glanici is located in the vicinity of St. Remy de Provence, in southern France. Glanum grew around the spring that was renowned for its healing properties. Many shrines were dedicated to the Mothers of Glanum, ancient Earth and healing goddesses. In Celtic beliefs, springs had a major role, and all the shrines were built next to springs.

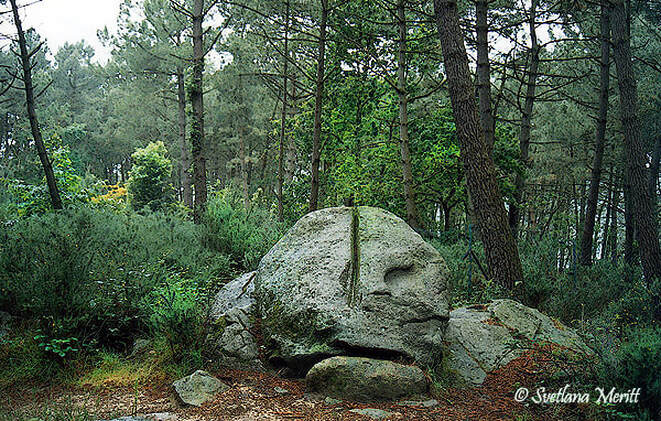

The natural setting of the ancient Glanum is … how shall I put it … disturbingly beautiful. I feel a mixture of awe before the majesty of the Alpilles Mountains that tower over the ancient ruins, and a strange feeling of well-being. The scattered columns rise like a fragment of Greece under the skies of Provence, confusing my brain. It’s as if many different feelings are stirred up in my body, clashing like ocean waves moved by different currents. In less poetic terms, I feel as if I’m in the middle of a strong magnetic field, and both poles are exerting a pull on my senses, which makes me feel disoriented. Glanum was positioned at the foot of a natural pass through the mountain range that stretches in an east-west direction for about fifteen miles. The buildings and temples were built along a north-south orientation, roughly the direction of the line that cuts through the jagged peaks. If the range were a dam for a lake, and this pass a sluice that was suddenly opened, imagine the power of the water that would gush through it. There is something of that feeling in Glanum—a feeling of an energy thoroughfare. One thing is certain: this was, and still is, a sacred site. It doesn’t matter that the original Celtic settlement was destroyed and built over by the Romans (as this juggernaut empire did everywhere else in the ancient world). The feeling of sacredness still permeates the air.  On this curved beach near the two distant rocks, a beautiful, naked woman rose from the sea foam. Flowers grew wherever she stepped. She brought joy and harmony, and sensual pleasure. Her name was Aphrodite. This is a part of the legend describing the birth of the Greek goddess of love and beauty on the western coast of Cyprus in the Mediterranean. Her role has come down to us as that of a licentious, vain, and powerful lover. But in Cyprus, she is much more than that. She is a symbol of wholeness and the union of the male and female principles, and she was identified with the fertility goddess Astarte. Her birth was a synthesis of opposites: out of violence and ugliness, she emerged as a bearer of love and beauty. (The myth goes like this: when Cronos, the youngest son of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth), hacked off the genitals of his father, the immortal penis fell into the sea and out of it Aphrodite grew.) Aphrodite was worshiped in many shrines on the island, but the main one was her temple in Palea Paphos. Her symbol was a conical omphalos (a navel stone). One of those has survived, blackened by centuries of libation with olive oil, and was in use until it was removed to the museum in Kouklia. Cyprus was my home for three years, and I swam many times around those rocks (the Cypriots believe you emerge more beautiful after swimming there!), and attended full moon meditations on the beach in honor of the Goddess, as Aphrodite is simply called in Cyprus. On a restaurant terrace up in the hills, I spent many afternoons with Dwight, silently watching sunsets that swept the sky on fire—the fire of love, it felt to me. This is a detail from le Forȇt de Paimpont in Brittany, France—the legendary forest where Merlin went seeking retreat and isolation, but instead fell in love with the fairy Viviane. The gorgeous fairy was so enamored with the great magician that she cast a spell around Merlin—a prison of air, if you will—so that he would never leave her. And Merlin, even though his powers were greater than those of his sweet enchantress, joyfully accepted the captivity.

Today not much is left of the once-huge and lush forest that covered the whole of central Brittany two thousand years ago. Heavy and steady logging of ancient trees, followed by a big fire of 1990, have reduced the magnificent forest to a mere 27 square miles (most of it privately owned). I searched in vain for Viviane’s Nest, where the fairy lived with Merlin; I searched in vain for Merlin’s tomb, because nothing is well-marked in this once-enchanted forest. Come to think of it, maybe that’s why I kept getting lost—the ancient Druidic spells may still be lingering in the foliage, rocks, and the very soil of the woods. |

Overview

All

|