|

When I stepped out of the car and saw this light-dappled forecourt flanked by old plane trees, the sun-drenched altar, and the statue of Notre Dame de Delivrance in the background, I felt as if I’d stepped into a dream. The sight in front of me looked just like a place from a dream I once had, down to the tiniest detail!

I was dumbfounded. I looked around the sanctuary bathed in peace and gentleness, and felt shivers running up my spine. There it was—the chapel, the statue, the altar, the plane trees—the whole scene just as it had been in my dream. Yet this was a real place, one of the old pilgrimage sites in the South of France, built in the early 14th century. A picturesque legend accompanies its founding. An invincible dragon used to terrorize the local population until a certain chevalier figured out how to kill it—by training a pack of dogs to attack its belly, the only place of its body that was unprotected. Unlike other instances of slaying a dragon in Christian iconography, performed by either St. Michael or St. George, this one was accomplished by a mere chevalier, although with the help of Mary. Hence the name – Notre Dame de Delivrance. For me, this legend carries more meaning than its surface story. Dragons symbolize Earth energies, also known as terrestrial currents, telluric force, serpent current, or the Druidic Wouivre. All these names have been used to denote and describe the animating but invisible power of the Earth, the vital Life Force on which all life forms depend. This telluric force was recognized and worshipped by ancient matriarchal cultures. The act of killing a dragon symbolizes a victory over the old, Mother Goddess worship and the subjugation of the forces of nature by the new order—the patriarchal religious system. But why I dreamt of this place, and how I could have “seen” it just as it was, has remained a mystery to me.

0 Comments

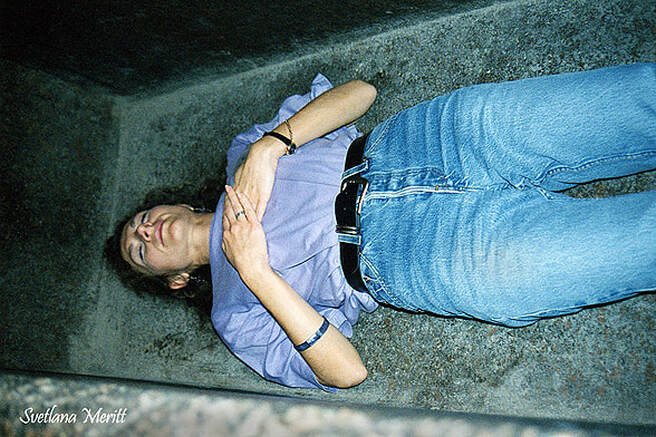

I consider it a great gift of life that Dwight and I have been awarded two hours of solitude inside the Great Pyramid. And not only solitude but complete darkness also, because of an unexpected power outage. We were practically locked alone inside the pitch-black pyramid!

That experience has changed me profoundly, just as it did one of the bravest men in the world—Napoleon—who appeared ashen pale and shaken after spending a night there alone. We don’t know what happened to Napoleon since he refused to talk about it for the rest of his life. But I know what happened to me: it helped me to overcome my fear of darkness and claustrophobia. Some fears have to be faced straight on … and walked into. Which is what I did when I faced the chamber engulfed in darkness, walked to the sarcophagus, lay inside, and turned off my flashlight... In the remote past, the King’s Chamber was used to facilitate the expansion of consciousness or as it is also called—initiation. It was designed for that purpose. Built to the proportions of Golden Section, it is also made entirely of monoliths of granite, which has a high content of quartz. Because of this, the King’s Chamber exudes a natural radioactivity, enhances sound, and gives off electrostatic charge, all of which has an effect on our consciousness. When you walk into the chamber, you also walk down the rabbit hole. Anything can happen on the inner planes—but not if the room is crammed with people. For that reason, I’m deeply grateful for those two hours of solitude. The Pyramids of Giza—perhaps the best-known image in the world, the signature of Planet Earth. To us, this is the sight of antiquity par excellence; to the ancients it was a futuristic sight, a creation of some inconceivably developed technology.

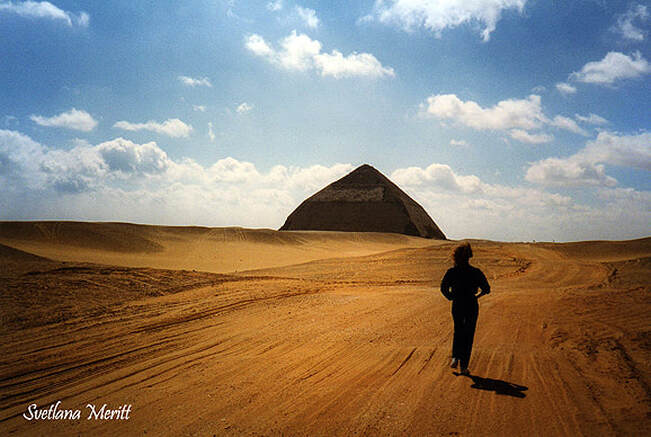

To fully grasp their effect, we have to imagine the pyramids as they were in their original state: cased in white limestone polished to a glass-smooth finish. To the ancients, they must have appeared as glittering prisms, rising out of the sea of sand. Without the casing, however, with the rough inner masonry exposed, the pyramids are like X-rays of beautiful women (to borrow John Anthony West’s witty analogy). It has been said that the Great Pyramid, also known as the Pyramid of Cheops, is the analog of the planet: in its measures and proportions, it reflects those of the Earth. It is also located in the center of gravity of the continents: it lies in the exact center of all the land area of the world. When reduced in scale, its shape has “magic” properties: foods placed inside of it maintain their freshness for a long period of time and razor blades get sharpened. The geometry of the pyramid was designed with a specific purpose, which we today can only speculate about. As many astronomers have noted, the pyramid is celestially aligned, making it a meridional instrument of a sort. Inside the pyramid are two chambers, several passageways, and four air channels. The shafts, as Bauval and Hancock showed, not only provided the interior with air, but also aligned with certain stars, such as Sirius, the brightest star in the Orion belt, and the North Star, as they were positioned in the sky over Giza around 2500 BC. The types of stone used for building were carefully chosen, too. The core of the pyramid consists of red granite with high content of quartz, iron, and magnetite—a type of stone that exudes a natural radioactivity. The outer limestone insulated the pyramid, keeping all the energy inside. By stepping inside, the priests of the past entered what was essentially a huge magnet. In the post "Inside the King's Chamber" I talk about what happened when Dwight and I were locked in for two whole hours—alone. Approaching the Bent pyramid at Dahshur from the silent immensity of the Saqqara desert, one gets an impression distinctly different from impressions of other pyramids. Its rhomboidal shape conveys a grounding feeling, the feeling of safe power.

Orthodox archaeologists consider the Bent pyramid built by Snefru, the first ruler of the Old Kingdom IV Dynasty—a mistake. Esoteric scholars think otherwise. In the archaeology, craft, and science of ancient Egypt (in particular during the Old Kingdom period), there were no mistakes; everything had a deeper reason, a symbolic function. The architects of Egypt employed the principles of sacred geometry in building pyramids and temples. Every structure had a function to perform, so the geometry was chosen accordingly—to facilitate through shape and number that purpose. Many researches have shown that different geometric shapes generate distinctly different energetic environments and, consequently, produce different effects on human body and psyche. For example, hospital patients placed in pentagonal rooms recover faster; trapezoidal rooms are particularly beneficial for schizophrenics; and blood coalesces quicker in vials of spherical shape. Since the Bent Pyramid is the only pyramid in Egypt that has a double-angled profile and double sets of chambers and double entrances, it seems obvious that this was a deliberately planned duality. So what is being conveyed through this unique shape? Here is a possible answer. The shape of the pyramid is based on the combined geometries of a pentagon and hexagon. The same structure exists in human DNA: the four base compounds are arranged in bonds of pentagons and hexagons. Since this ratio of the pentagon to hexagon (5:6) can also be found in the Earth, the Bent Pyramid seems to echo human and planetary bodies. Furthermore, because all living organisms are pentagon-based while non-living objects are hexagon-based, symbolically the pyramid may be representing a balanced relationship between both forms—animate and inanimate. There is a whole language hidden in numbers and shapes, but we’ve forgotten how to read it. The structures of ancient Egypt are there to remind us of that language and help us remember it. To appreciate fully the achievement and importance of this pyramid, the first to be built in Egypt, you have to use your imagination. So imagine, if you will, the stepped surface completely clad with blocks of white limestone, shimmering with light in the vast, yellow sea of the Saqqara desert. And imagine a surrounding wall, also built of white limestone, designed in such a modern style that it served as inspiration for some ultra-modern public buildings in Arizona and Spain. This circular wall, more than a mile in circumference, enclosed other remarkable buildings: a funerary complex of King Zoser, several smaller pyramids, many tomb-chambers, and a causeway. All the features—carved hieroglyphs, bas-reliefs, a colonnade, rooms covered with unique blue tiles of exquisite beauty—were executed with superb craftsmanship.

And now comes the twist: this is the OLDEST stone complex in the world (after the Sphinx), the biggest ever built by a single ruler, AND it was carried out with such perfection of craftsmanship that was not surpassed in the succeeding 3000 years of Egyptian Pharaonic history. The funerary complex of Zoser appeared in full mastery and perfection of architecture and art in the history of Egypt. Which would be like starting the history of automobiles with a Ferrari! Ancient Egyptians believed that all their sciences, religion, writing, and architecture—in brief, their whole civilization—was transmitted from an earlier race by a group of beings referred to in ancient texts as Shemsu Hor, the Followers (Companions) of Horus. The Western esoteric tradition (which started with Pythagoras and Plato) attributes the origin of these beings to the Atlantean civilization, which was destroyed in a series of cataclysms around 10,000 BC. Walking around this funerary complex—in and out of the pyramids of Zoser and Unas, the exquisitely-carved tombs, through the colonnade and causeway—I couldn’t but register a completely different feel of this place compared with the Giza plateau and the three major pyramids there. Perhaps because so much more art work is preserved here, there was a feeling of richness of energy, an almost joyous, light purposefulness. Compared with the grandiose and removed impersonality of Giza, the Saqqara complex almost throbbed with beauty.  Two streams flow out of Glastonbury Tor (the sacred hill I wrote about in my previous post)—the Red and White Spring. They rise closely together and share the same source under the Tor Hill, yet their mineral content is entirely different. The White Spring contains calcium, while the Red or Blood Spring is rich in iron. The Red Spring (in the picture) flows through the beautiful gardens of Chalice Well Trust, an esoteric organization created by a businessman and an extraordinary visionary and psychic, Wellesley Tudor Pole, to preserve the sacredness of the spring and surrounding land. The healing properties of the waters have been known since the remote past. But there is much more to these springs than just their mineral content which promotes healing. The springs flow out together from one of the most sacred hills in Britain—the Tor—which has most unusual energetic properties: two earth currents weave around the slopes to make a three-dimensional maze (see my previous post). As a result, the underground water is subjected to an energetic spiral vortex at all times. And water, it has been shown, reaches its highest level of ionization when in a rapidly moving vortex. Furthermore, the distillation of these springs from the subterranean aquifer has been compared to the alchemical process conducted within the retort (the Tor serving as an alchemical retort or alembic). The red and white colors of the two springs symbolize the interplay of red and white substances in alchemical work. In medieval and Renaissance European alchemy, red and white fluids represented two opposing principles: fire and water, sun and moon, or blood and milk (or sexual fluids). Their interplay, transmutation, and eventual “marriage” (alchemical wedding or coniunctio) produces the Philosophers’ Stone—the process that transmutes the base metal of matter/body into the refined gold of spirit. When I made the pilgrimage to Glastonbury and stayed at Chalice Well, I didn’t know all of this. I usually prefer to have the experience first, then to read about the site I visited afterwards. This is why when I strolled the lush gardens at dusk, alone under the darkening canopy of leaves, I could open to the energy of the place without any expectations. I sat by the source of the Blood Spring in complete darkness and felt the forces of nature all around me. It wasn’t exactly pleasant; in truth, it was almost frightening. But then again, the powerful sacred places that stimulate inner transformations are not supposed to feel pleasant. Their function is to stir, break down, trigger crises, awaken, or purge. Because in all the ancient mystery traditions, the first requirement of an initiatory journey is a visit to the underworld—the symbolic descent into the cavernous depths of the earth. Sitting by the dark opening of the Blood Spring at night reminded me of that stage of the journey, the journey I went through several years ago, the journey I’m writing about in my spiritual travelogue Meet Me in the Underworld.  The unusual conical shape of Glastonbury Tor emerges from the Avalonian landscape like the crouched back of some prehistoric animal. A lonely tower rises from the top of the mound, beckoning travelers. Man-made terraces, painstakingly carved in a very distant past, add an aura of mystery to this already extraordinary place, a hallmark of Glastonbury. The Tor Hill is one of the most recognizable landmarks on the map of sacred sites of England. Its fame is based on the configuration of powerful earth energies that spiral around the hill. It’s been referred to by many researches as a “vast electrical transformer” and a “generator and transmitter of earth energies.” The Tor is like an energy vortex. As the dowser Hamish Miller has discovered, two earth currents of different polarities—which he dubbed Michael and Mary—weave in a courtship-like dance up the slopes to meet and “mate” on top of the hill, at the place where an ancient altar still stands. The enigmatic ringed terraces coincide with the path of these energies. A survey of the Tor has shown that there are seven of the rings, which are joined in such a way as to form a continuous pathway towards the top of the hill. Which makes the Tor an actual three-dimensional labyrinth! The seven-layered labyrinth, the antiquarian John Michael points out, symbolized the classical Mysteries. The solitary tower in the picture is all that remains from an old church destroyed in a 12th-century earthquake. The church was dedicated to St. Michael, the patron saint of high places and sacred hilltops, but also the initiator who has power over the underworld. According to ancient legends, the Tor was believed to be hallowed and to contain the entrance into the underworld in an underground cavern. Incidentally, modern speleologist have discovered caves under the Tor, which seems to confirm the legend of the hallow nature of the sacred hill. And to top the list of extraordinary features of the Tor, the axis of the hill is algined with a ley line which also traverses the Glastonbury Abbey, then continues on its way to the megalithic site of Avebury. From whichever point we look at the Tor—either energetically or symbolically—it is indisputable that this hill was a sacred place, an ancient center of initiation.  These remnants in the picture are all that is left of the powerful Glastonbury Abbey, once the foremost center of Christianity in Great Britain and a highly popular place of pilgrimage. The sacredness of Glastonbury is based on many myths and legends, but also on the fact that for 3000 years it was a center of religious power. According to the most prevalent legend, it was here that the first Christian church in England, and possibly in all Christendom, was founded. The deed is attributed to St. Joseph of Arimathea, who is said to have traveled from Jerusalem through southern France and Cornwall to the sacred isle of Avalon, where he built the original wattle church in 63 A.D. The legend goes on to say that with him, St. Joseph brought two cruets and a chalice that Jesus used at the Last Supper—the legendary Holy Grail. In addition, St. Joseph was accompanied by twelve holy men, who built twelve huts around the wattle church. Now, we may read this legend at a surface level, but we may see it at a deeper level as an allegory, connecting Christianity with the principles of Druidic belief system which it replaced, as well as the Arthurian myth. The pre-Christian Celtic societies (and many others, for that matter) were based on the traditional code of cosmology centered on the number twelve. This number, issuing from the twelve signs of the zodiac, was the emblem of the sacred order which provided the structure for organizing social order—architectural proportions, measures, and music were all based on this numerical canon. Hence, Odysseus led twelve heroes, Hercules conducted twelve labors, King Arthur was accompanied by twelve Knights of the Round Table, Charlemagne’s court was composed of twelve nobles, and even Jesus had twelve apostles. The holy atmosphere that the pilgrims experienced at the Abbey was created by the “priestly arts”—the knowledge of sacred measures and their influence on human psyche. An important part of these priestly arts was music. Music or sound, being frequency, has the power to induce higher states of consciousness (or lower, as in the case of some modern forms of music). In the early days of Christianity in Britain, known as the Celtic Church period, a new liturgical chant was introduced: a twelve-part chant, based on the twelve notes of the chromatic scale. These chants were performed around the clock in every Christian community, as it was believed that the sacred music sets the tone for the whole country. One of those perpetual choirs was in Glastonbury Abbey, where monks maintained the chanting day and night. (Incidentally, the word “enchantment” comes from “chanting.”) We can only try to imagine what effect this practice had on subtle planes. The frequencies emitted by perpetual chanting all around the country created something like warp and weft, an invisible scaffolding that held together not only social order, but also higher beliefs and principles. And the human psyche was immersed in those sacred frequencies as if in an invisible ocean. I can’t but remark that today we’re surrounded by the perpetually-emitting frequencies of our wireless technology that affects our psyche—for better or for worse. In remote times, when the Ice Age glaciers receded, this Somerset landscape was a marshy inland sea, an extension of the Bristol Channel. The sea was dotted with island hills, seven of which were held sacred. And among those seven sacred isles, the Isle of Avalon (today’s Glastonbury) had a prominent place.

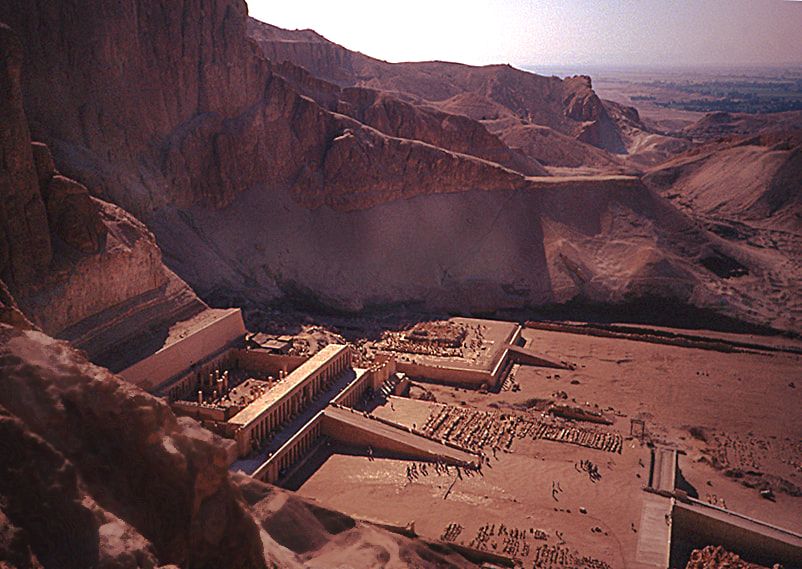

In Celtic mythology, this whole plane was referred to as the Summer Land (hence Somerset), the realm of perpetual youth and summer, where plants yielded fruit all year around—Elysium, a reflection of heaven on earth. It was here that the souls of the deceased arrived for their deserved rest, play, and feasting before rebirth. Set in the heart of this paradisiacal, sacred landscape was Avalon, called in Celtic the “Isle of Glass” (hence Glass-town-bury). In Welsh, Glastonbury has another etymology: it means the “Isle of Apples,” apples being fruits that grow in paradise. Mythologically, a glassy isle is a place of enchantment, a place where the veil between the worlds—the invisible world of the spirit and that of matter—dissolves. A place where the entrance to the Otherworld is to be found. The rulers of such an enchanted landscape are, naturally, fairies. And the main among them was Morgan le Fey (“the Fairy”), whose abode was the Glass Castle on the Isle of Avalon. Morgan le Fey, also known as the Lady of the Lake, is an aspect of the Divine Feminine closely connected with the processes of death and rebirth. It was Morgan who received the dying King Arthur to escort him on his journey into the other world. According to the legends, Arthur’s sword, Excalibur, was made on this island and was guarded here. Standing on top of Glastonbury Tor (where this picture was taken), with the panoramic view of the whole valley at my feet, I imagined the misty, watery landscape with reed beds, and boats gliding between isles. There is something special about Glastonbury and this view, a certain mystical quality of the light over the landscape… Glastonbury has the power to stir up memories of some distant, golden past. Hatshepsut was the only Egyptian queen who proclaimed herself a pharaoh, a title reserved for men of royal blood only. Because of this unprecedented act, she was (and still is) one of the most controversial Egyptian rulers. She assumed the throne after her pharaoh husband/brother died in the 15th century BC, and established a successful reign. Upon her death, however, her inscriptions were obliterated and the reliefs in which she was portrayed effaced in an effort to erase the memory of her—so much had she offended pharaonic protocol and tradition. Hence, we know very little about her.

The greatest record of her life and reign is her mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari, near Luxor in Upper Egypt. It is a unique work of architecture, just as her pharaonic reign was unique. Built on the spot that was sacred to the Goddess Hathor from much earlier times, the temple was a healing center as well. But its uniqueness actually lies in its design. With its clean lines and a minimalistic and spare geometry, this temple is the only one in Egypt that is so organically integrated into its natural setting: it is partly built against the cliff face and partly cut into it. Because of this, the temple has a very modern feel. It has been considered one of the architectural masterpieces of the world ever since it was built, when it was given the name The Most Splendid of All. Indeed, from the vantage point atop the surrounding hill from where I took this shot, the simple elegance and harmony of its lines are even more striking. Emerging out of the copper-baked cliff, the terraced temple reaches out into the valley like a flock of birds with outstretched wings. |

Overview

All

|